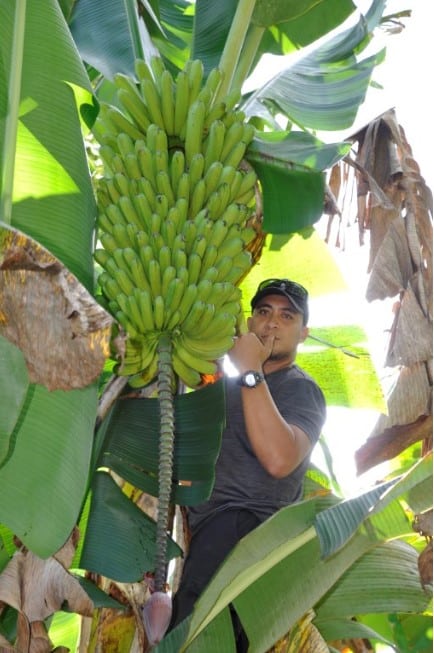

As the huge commercially grown banana crops around the world are facing collapse because of a devastating disease, a survey has just been completed of the varieties of plantain (utu and Maori) bananas growing on Rarotonga and Aitutaki.

The survey team of Ministry of Agriculture staff was led William Wigmore – the Director of Research – and included global banana experts from Hawaii and France. In the course of the survey they identified between 30 and 40 different varieties growing here. Of particular interest were plantain type bananas – utu – some of which have extremely high nutritional value.

William Wigmore says the survey group collected banana shoots from the hills and valleys inland, and sent them off to a banana research centre in Belgium for preservation. Although that facility has the largest collection of bananas in the world, it is short of some Pacific varieties.

Shoots were also sent off to the Centre for Pacific Crops and Trees in Fiji, which is another preservation laboratory, for Pacific crops.

Those centres in effect provide insurance cover against the loss of the plants they hold, in their home countries. William Wigmore says he’s not concerned about sending varieties of our plants away for safe keeping, saying we get back more in return than we put in to such places.

He says, “In 2004, the Cook Islands became a party to the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, which facilitates the conservation and use of plant genetic resources.’

“The materials sent to these centres can be repatriated in the event we lose them as a result of a natural disaster or a pest attack. In fact about 20-years ago, we sent some varieties of Taro from Rarotonga and Pukapuka to Fiji as we feared those varieties might disappear from our islands. Some have since disappeared, such as the variety known as ‘Tiitii Teatea’. Fortunately, such centres have been established to protect these varieties which we can repatriate at anytime. More and more varieties of important crops worldwide are under threat of disappearing as a result of land use changes, changing diets and changing climatic conditions.”

He cites another case where the single variety taro crop in Samoa was hit by disease in 1993 and virtually wiped out – one of the great dangers of a single variety crop. Taro plants held in Fiji resistant to the disease were used to rebuild the food source that was lost.

Of the 30 to 40 varieties of banana found in the Cook Islands, about half are regarded as indigenous having probably been brought here in very early migrations by our voyaging ancestors; others have been introduced in more recent times.

It’s estimated there are over a thousand, maybe thousands, of different varieties of banana around the world. But the vast tonnage of bananas grown commercially is largely based on one variety and therein lies the problem.

Like the Samoa taro crop wiped out in 1993, the Cavendish banana the world’s commercial crops are based on, has contracted a disease – commonly known as Panana disease – that is decimating the single variety plantations. The fungus has proved resistant to attempts to control it and has spread to crops in banana producing countries around the world.

An example of the devastation is a huge – six-thousand-hectare – plantation, being developed in Mozambique in southern Africa. The developers and the Mozambique government, had high hopes of the bananas providing large scale employment and a shot in the arm for the local economy. The project had in place protection measures to stop the fungal disease invading the plantation, including chemically washing vehicles and machinery entering the site. But the disease got in. Probably on the boots of two workers who came from an infected area.

The plantation has now been reduced to two-hundred hectares of badly wilted – a sign of the disease – banana plants.

Another variety resistant to Panana disease has been identified, but it will take years to replicate the commercial numbers needed.

Since the humble banana became one of the world’s favourate fruits, the international banana market has collapsed twice. The first time in the mid 1950s when it was based on a variety called Gros Michel; and the collapse that is taking place now. The current most popularly marketed banana is called the Cavendish banana, named after Cavendish House in the UK where it had been collected and preserved. But now it too – as a solo crop, grown in huge numbers – has fallen prey to disease.

It is tempting to think that in our 30 to 40 varieties we might have the answer, but that is unlikely to be the case. The replacement banana will need to have certain qualities.

Of course it’ll need to be resistant to the fungal Panama disease. It’ll need to be capable of being grown in huge tonnages, have a long shelf life, and handle a fair bit of sometimes rough handling as it is harvested, packed and then shipped to a probably distant destination, where it is then unpacked, induced to ripen and go yellow, ready for sale.

While we’re waiting to become ‘banana billionares’, we should probably just keep eating our mostly organically grown, tree ripened and perfectly sweet bananas; maybe stepping up production to feed our growing number of visitors, who once they’ve tried them at their best often swear they won’t eat another industrially grown banana ever again.

Bananas are believed to have originally come from south Asia and are now grown in about 135 countries around the world. More than 50-million tons are sold commercially annually, and a banana is technically a berry.

In order to see the full report please click on the link provided: https://mailchi.mp/db5dc7d91b21/musanet-newsletter-december-2019